Breach Notification , Incident & Breach Response , Security Operations

Breach Alert Service: UK, Australian Governments Plug In

Both Governments' Domains Now Centrally Monitored via 'Have I Been Pwned'

Data breaches of online services involving usernames and passwords can have an immediate knock-on effect. Attackers can take the stolen credentials and try them on other services. If users have reused their credentials across services, attackers can potentially compromise many more of their accounts.

See Also: Are You APT-Ready? The Role of Breach and Attack Simulation

For sprawling organizations, such as governments, multiple sets of reused passwords could create even bigger problems, allowing attackers to access large data sets. For responders, acting quickly remains essential. But governments' very size can make that difficult.

To help, however, two government organizations - the U.K.'s National Cyber Security Center and the Australian Cyber Security Center - have begun a new program using Have I Been Pwned, a data breach notification service created by Australian developer Troy Hunt.

Some branches of the U.K. and Australian government have already been using HIBP. Under the new program, however, the governments will use the service to monitor every government domain, together with a select number of quasi-government sites that fall under their purview.

"Part of what both of these organizations in Australia and the U.K. realize is that they need to work better with the private sector as well."

—Troy Hunt

The move will give the U.K. and Australian governments a more complete view of the breach threats they face, Hunt says.

"All of these sort of independent monitorings will roll up into one centralized view, which should reduce a lot of duplication of effort," Hunt says. "The other thing is there's going to be a heap of other government departments that never used the service at all that will now be able to be monitored."

The organizations are able to query any of their domains on demand via an API. They can also use an instant notification feature that notifies an endpoint, designated by each government, as soon as an email address registered to any domain they oversee gets added to HIBP.

Those two features are part of a commercial offering within HIBP, but Hunt is letting the governments use it for free.

"Part of what both of these organizations in Australia and the U.K. realize is that they need to work better with the private sector as well," Hunt says. "They want to get more information out there around how individuals and organizations can do better to protect themselves. I'm really supportive of what they do."

Breach Alerts

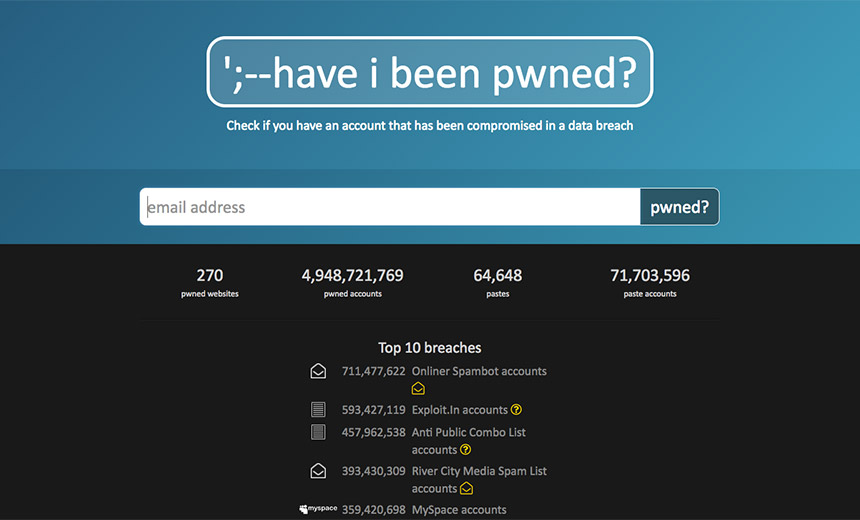

Launched in 2013, HIBP has grown in popularity with the surge in the number of data breaches that have become public. Users register their email address, and if that email address turns up in breach, HIBP sends an email alert with a description of the breach.

It's also possible to get notifications for email addresses affiliated with a domain, but domain owners must first verify their ownership of the domain. Hunt says 110,000 domain owners have verified their domains with the service.

HIBP doesn't catalog every breach, which would be infeasible. But it includes many of the largest breaches that have come to light in the past few years, including incidents involving LinkedIn, Dropbox, Adobe as well as several large compilations of usernames and passwords that have circulated on hacking sites.

HIBP now covers 270 breached websites and contains close to 5 billion leaked records. Users only learn if their email address was in a breach. The service does not provide the password that was used on a particular service or even a hash of the password.

But if someone uses a password manager to maintain unique passwords for every site they use - as many security experts have long recommended - then they would be able to figure out which of their passwords the breach exposed, and know to change it anywhere else they might have reused it.

Limits of Monitoring

Hunt says governments will only be able to monitor the sites that they own or a small number of other domains that are still in their scopes.

For example, the Australian government will be able to monitor all of their .gov.au domains, but also that of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, which is the country's national science and research agency.

To put it another way, the governments can't search for any email addresses that may have appeared in a breach. Hunt says it's an important point to make, particularly for those worried about government surveillance.

"We do want these people [governments] keeping us safe on online," Hunt says. "There's a lot of work that our government do in cyberspace that's enormously valuable."